Pierre Cliche, Visiting Professor

École nationale d'administration publique

pierre.cliche@enap.ca

A budget is a document in which a government presents its revenue and expenditure forecasts for the coming year and that requires the approval of parliamentarians before it can be implemented.

The word “budget” comes from the Norman word bougette, meaning little bag, purse or satchel. It eventually made its way into English, where it came to signify not only the bag itself but also the contents. Following a slight phonetic shift, bougette became “budget,” in reference to the financial documents that the Chancellor of the Exchequer carried to Parliament in his bag and read before its Members (Schick et al., 2009, p. 43).

A budget is a plan that specifies how much money is available for a given period and the expenditures to which this money will be allocated. As a rule, it is drawn up for one year, and indicates what the government's financial position will be at the end of the year if all goes according to plan. Essentially, it is a forecast document.

A budget is made up of two, highly interdependent components – namely, revenues (funds that will be collected) and expenditures (funds that will be spent). The resources that are generated by revenues are used to finance anticipated expenditures, whose level is usually set on the basis of anticipated revenues. Therefore, lower-than-expected revenues can make it hard to maintain a particular level of spending or can even lead to a reduction in spending or to a deficit, while higher-than-expected revenues make it easier to sustain projected spending and can lead to a surplus or to an increase in spending or both. In other words, a budget is a document where the relationship between revenues and expenditures is not neutral. Any imbalance between the two sides of the equation will cause a reaction or an adjustment, especially when revenues are not high enough to sustain expenditures.

Unlike households and businesses, which are under no obligation to prepare a budget, let alone make it public, all democratic governments are required by law to table one. Moreover, all withdrawals and expenditures from public budgets must be officially approved. In other words, public budgets do not simply serve information purposes, but are legal in scope: no expenditures can be incurred until the budgets are adopted by the appropriate authorities following a set procedure, and the expenditures cannot exceed authorized amounts. For the private sector, budgets are one of several financial management tools, although they serve mainly as a compass.

Budget process

A budget is the end product of a strategic planning and operational programming process aimed at generating and deploying resources for government action. Even though it has to focus on a given budget year, it includes measures whose impact is felt well beyond that year (Cliche, 2009, p. 295). Indeed, certain government measures cannot be designed for only a one-year timeframe, as it takes several years to fully implement them. Nonetheless, to acquire a realistic understanding of the implications of an annual budget, there has to be some way of defining the duration of the measures it contains and to base these measures on multi-year revenue and expenditure forecasts.

Therefore, a medium-term budget framework is prepared to show the cost of activities announced or under way and their impact on future budgets. Basing revenues and expenditures on forecasted economic trends makes it is possible to factor in the impact of decisions beyond the current year and obtain an overall picture.

Figure 1: Budget process

Budget cycle

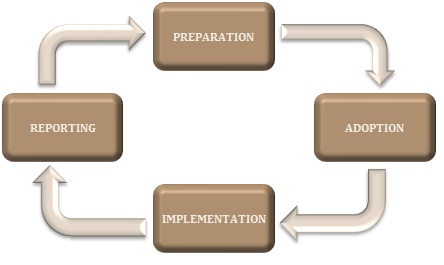

Governments prepare budgets on a recurring basis, using the same process year after year. The process comprises main four stages: preparation, adoption, implementation and reporting.

Figure 2: Stages in the budget cycle

Preparing a budget involves gathering all the information required to determine the resources that a government will need to carry out its operations and achieve its objectives. Revenue and expenditure estimates are made and validated at different levels. The information is then compiled, consolidated, and presented in an appropriate format. The budget preparation stage takes place during the year prior to the period covered by the budget and lasts eight to ten months.

In Westminster-style democracies, once a budget has been approved by the government authorities, it is submitted to the legislature for adoption. It undergoes careful scrutiny by the members of parliament, who are usually allowed, at this point, to put questions directly to ministers in order to obtain clarifications about the appropriations that will be allocated to the latter. A vote is then held to approve the budget and authorize its implementation.

During the budget implementation stage, the various branches of government are informed of the envelope they will have for the year that has just begun. These funds will be gradually placed at their disposal, in accordance with each branch's projected rate of spending and specific project needs. This is the stage where the government fulfils its financial commitments by disbursing the promised amounts. Periodic statements of revenue and expenditure are prepared to measure the difference between the budget forecasts and reality. Changes can thus be made to the budget while it is being implemented in order to adjust it to changes in the overall economic situation. Generally speaking, the budget implementation stage continues a few weeks or even a few months into the subsequent fiscal year so that all accounts receivable for the year just ended can be submitted and settled.

During the last stage – i.e., the performance monitoring and reporting stage – the final revenue and expenditure figures for the year just ended are compiled and audited internally by public bodies and then consolidated for the purpose of preparing the government's financial statements or public accounts. Next, these financial statements or public accounts are audited externally by an independent public authority, designated for that purpose. Parliamentarians are able to assess the management of public funds when government departments and agencies table annual reports describing what they have achieved with the funds placed at their disposal and the problems they encountered along the way.

The budget cycle thus covers three separate years and concerns, during any given year, three different budgets at different stages in the cycle: the budget for the year just ended, which must be reported on, the budget for the year under way, which must be implemented, and the budget for the coming year, which must be prepared.

Types of budget

There are several different types of budget: operating or current budget, capital or investment budget, and cash or cash flow budget. Each one meets a specific need and is essential to proper planning of a government's financial activities. All of these types of budget exist in one form or another in governments' general budgets.

• Operating budget

An operating budget comprises the expenditures and revenues needed for day-to-day management of production and service activities. It is divided into programs or operating units that engage in activities and services for specific purposes. It indicates the nature of expenditures incurred (remuneration, procurement or lease of goods and services, transportation, transfers, etc.), the funds needed to repay the debt, and contributions to reserve funds. In short, an operating budget is used to purchase consumables and pay the government's current expenditures as a whole.

• Capital budget

A capital budget comprises revenues and expenditures that affect public assets. The useful life of the assets covered by the budget as well as the time required to carry out the associated transactions often exceed the budget year. A capital budget presents a list of priority needs in regard to fixed assets (buildings, facilities, roads, airports, etc.) for the coming years. It also identifies other types of necessary durables, such as movables, electronic office equipment, vehicles and miscellaneous equipment. Covering capital expenditures, capital budgets are used to plan for the infrastructure needed to maintain or improve public services.

• Cash budget

Cash is the total amount of liquid capital (i.e., money available immediately) that is required to cover ongoing expenses as a whole. Cash problems arise especially when cash inflows occur after an activity has been carried out and costs have already been incurred for the activity concerned. To avoid this type of problem, it is necessary to draw up a cash flow plan or a cash budget, which provides a forecast of real-time cash inflows and outflows. To effectively manage the coming year, it is not enough to simply have a balanced budget. Payments must also be made as they come due, which requires amassing enough liquid assets beforehand or having large enough credit lines.

Government plans can rarely be implemented unless resources are allocated to them and the use to which these resources are put is presented in budget documents. In fact, all of the actions taken by a government are summarized in each of the budgets it tables and adopts. A budget is thus a public document of prime importance that serves a range of purposes. First of all, it is a planning tool in that it obliges governments to define objectives and devise means to achieve them while adhering to their policy directions (strategic planning) and factoring in actual conditions (strengths, weaknesses, possibilities). A budget is also a communication tool, as it disseminates government policies and objectives and helps to ensure that the policies and expectations of each administrative component are consistent and compatible. Moreover, a budget serves as a coordination tool, for it encourages individuals to work economically, efficiently and effectively toward their organization's objectives and fosters consistent decisions and policy directions. Lastly, it serves as an instrument of control in that it helps to monitor differences between forecasts and actual results and to identify the reasons for these differences, thereby making it possible to carry out the necessary adjustments.

Bibliography

Allen, R. and D. Tomassi (2001). Managing Public Expenditure: A Reference Book for Transition Countries, Paris, OECD.

Cliche, P. (2009). Gestion budgétaire et dépenses publiques : description comparée des processus, évolutions et enjeux budgétaires du Québec, Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Schick, A. and al. (2009). Evolutions in Budgetary Practice, Paris, OECD.

World Bank (2007). Budgeting and Budgetary Institutions, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/BudgetingandBudgetaryInstitutions.pdf (last retrieved in July 2010).

World Bank (2000). Manuel de gestion des dépenses publiques, Washington, Banque mondiale [also published in English as Public Expenditure Management Handbook, Washington, DC, The World Bank].

__________________________

Reproduction

Reproduction in whole or part of the definitions contained in the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Public Administration is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged.

How to cite

Cliche, P. (2012). “Budget,” in L. Côté and J.-F. Savard (eds.), Encyclopedic Dictionary of Public Administration, [online], www.dictionnaire.enap.ca

Legal deposit

Library and Archives Canada, 2012 | ISBN 978-2-923008-70-7 (Online)