Bachir Mazouz, Professor

École nationale d'administration publique

bachir.mazouz@enap.ca

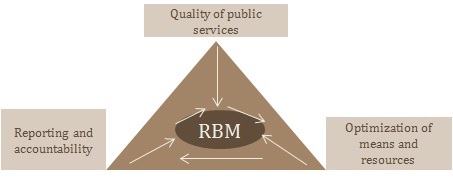

Management by results (MBR), or results-based management (RBM), is a government performance management framework with three logically linked focuses: the quality of public services, the optimization of available means and resources, and the accountability of public sector managers.

Figure 1: The three focuses of management by results

Source: Mazouz and Leclerc, 2008

MBR is based on the principle of performance commitments. Indeed, managers cannot simply set objectives, as in management by objectives, but must also undertake to achieve those objectives. Managerial action is thus subject to an obligation of results (or a performance commitment) and should ensure, or at least facilitate, the achievement of results targets. The three constraints that have to be managed within the context of this approach are the scarcity of the resources and means placed at the disposal of managers, compliance with legal and administrative rules, standards and practices, and the satisfaction of citizens, viewed as clients, users and recipients of public services (Mazouz and Leclerc, 2008).

Generally speaking, MBR makes results central to managerial and organizational action. For Mazouz and Leclerc (2008), the concept of results refers to four specific and measurable categories of outputs that the managers of public service supply systems must consider in their quest for performance: delivery results, management results, policy results and overall improvement results (see the results categories discussed further on in this definition).

A number of management tools are widely used in MBR, including strategic planning, annual management and continuous improvement plans, systematic measurement and evaluation, management scorecards, performance indicators, benchmarking, process reviews, annual management reports, accountability reporting, management agreements and performance contracts (agreements) between the different levels and stakeholders involved in government action. These tools enable public sector managers to plan, organize, make decisions about, control, monitor and assess the quantity and value of the results achieved under their management mandate (Mazouz and Tardif, 2010).

The terms of reference for MBR have been developed gradually over the years on the basis of initiatives aimed at modernizing public governance systems in certain OECD countries. The United Kingdom, New Zealand, the United States, Australia, Canada and, more recently, Quebec and France were the first to structure their public management practices around the concept of results. The different approaches tested by these countries continue to be a model for experiments under way elsewhere.

The first generation of programs designed to modernize the machinery of public governance (because of its numerous economic, budgetary and financial principles) was aimed at optimizing government resources without really taking charge of the other aspects of public organization. Management by objectives was the logical response to the efficiency concerns of administrative units. Generally speaking, modernization programs designed to restore order to public finances have generated more frustration and mistrust among government employees than they have improvements in the quality or cost control of public services (Mazouz and Tardif, 2010; Mazouz and Leclerc 2008; Mazouz and Tremblay, 2006).

The Fulton Report, published in the United Kingdom in 1968, severely criticized the management of government organizations and recommended that accountable management be introduced in each of the government's administrative units. To address serious and persistent financial and budgetary problems, the Financial Management Initiative was adopted in 1983 and then strengthened in 1987 with the publication of a report by the Efficiency Unit entitled Improving Management in Government: The Next Steps. Since this report focused on public management, many experts now believe it heralded the advent of a public management framework based to a lesser extent on means and procedures than on the results achieved by government organizations (Deschênes and Sarault, 1994). This report was in turn strengthened in 1991 by the Citizen's Charter (declaration of services to the public), which required all public organizations to draw up and publish quality standards for the services they offered to citizens. Because of the difficult budgetary context, bureaucratic rigidity and the emphasis placed on the results of government action, the Civil Service Act was amended in 1992, making it possible for large government agencies to negotiate collective agreements with unions.

Administrative reforms launched in New Zealand in 1988 were justified, as with the British model, by considerations tied to the performance and accountability of the various players in the public service. These reforms, which rounded out results-based budgetary and financial mechanisms, were based in particular on a radical overhaul of procedures and on greater managerial autonomy – a prerogative called for by public sector managers. The public service supply structure and its official management framework were the object of bold legislation that helped to change the relationships between the different levels of government action. Public organizations in New Zealand went from being governed by an administrative management framework where central hierarchical control was dictated by bureaucratic considerations to being part of a system where decentralized responsibilities was granted on the basis of the results that these organization targeted, achieved and had to improve. With the decentralization of responsibilities came the delegation of budgets and thus greater reliance on the role of the chief executives of government departments and Crown entities. Furthermore, developing the strategic character of budgets led to changes in planning, which began to be conducted on a multi-year basis.

Seriously concerned by the public debt burden and strongly inspired by experiments in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, the Government of Canada launched, in 1989-90, Public Service 2000, a program focused on innovation, client services and the accountability of public servants. In 1995, encouraging spinoffs led to the institutionalization of the principles of an official results-based management framework, namely:

-

establishment of measurable results targets for all government programs and projects;

-

systematic assessment of the results achieved;

-

communication with Members of Parliament for information purposes and for analyses of the gap between anticipated and achieved results;

-

publication of results targets, actual results and the gap between the two so as to foster the dissemination and adoption of best management practices and improve the performance of public organizations.

At the organizational level, implementing agencies were set up on a trial basis and, as of 1998, their management practices, particularly those related to Performance Reports and Reports on Plans and Priorities, were extended to all federal government departments and agencies so that they could assess their results.

MBR was institutionalized in Quebec in May 2000 with the coming into force of the Public Administration Act. Indeed, this piece of legislation made MBR the official “management framework.” In 2005, an evaluation study by researchers Côté and Mazouz concluded that the following reporting processes and management tools were relatively effective: declarations of services to the public (service statements), strategic plans, annual expenditure management plans, annual management reports and continuous improvement plans.

In France, the MBR framework institutionalized by the government includes the following practices and tools: performance contracts, possible easing of a priori control, general reviews of public policies and programs, widespread use of results assessment, and a results-based review procedure for new programs.

Studies of the official mechanisms introduced in OECD countries have shown that MBR stems from a managerial trend that took root beginning in the late 1970s. This trend is based on an institutional pact justified by the search for managerial autonomy, which is now essential to the renewal of public governance. Without radically calling into question the values of public administration, managers are focusing on the organizational and managerial factors that make public action effective and efficient. The managerial autonomy required by MBR should improve the managerial and organizational capabilities of management teams and employees in the public sphere. Autonomy levels must be assessed throughout management cycles on the basis of the leeway required by public sector managers so that they can obtain management tools for setting results targets tailored to their organization's mission, planning activities related to those targets, optimizing resources, and measuring and assessing their actual performance according to parameters based on the physical and perceptual attributes of the outputs that they themselves have helped to identify, define, plan, implement, control, monitor and improve (Mazouz and Tardif, 2010).

By 2010, after three decades of experimentation, MBR had become the official management framework of many governments, namely, that of the United States, following the coming into force of the Government Performance and Results Act in 1993; that of Quebec, following the application of the Financial Administration Act in May 2000; and that of France, following the enactment of the Loi organique sur les lois des finances in 2001. All of these laws were drafted and passed after 5 to 10 years of more or less voluntary experimentation.

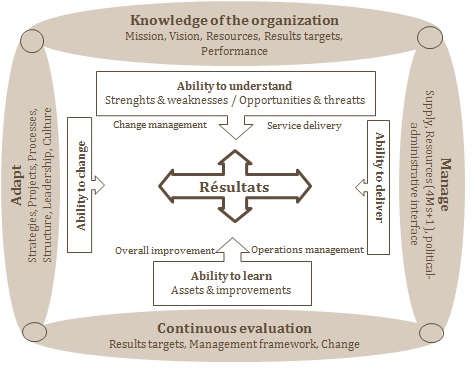

The model chosen for the present definition of MBR stipulates that public organizations that engage in a process of continuous results improvement must first fulfil the following four requirements:

-

Organizational requirement: public organizations must understand their particular situation – i.e., that they are individual entities with distinct purposes, politicized objectives and limited resources, as this will enable them to understand their strengths and weaknesses, the threats they face and the opportunities their managers must seize in order to enjoy more autonomy in negotiations with headquarters;

-

Managerial requirement: public organizations must also adopt an official management framework focused in particular on the quality of resource management, the political-administrative interface and the supply of public services, as this will enable them to deliver services;

-

Adaption requirement: public organizations must adapt their organization by renewing their strategies, processes, projects, structures, culture and leadership, as this will enable them to change;

-

Evaluation requirement: public organizations must systematically evaluate themselves as well as their management framework and ability to change, for this will enable them to learn and to make improvements.

Figure 2: Results categories and their determinants

Source: Mazouz and Leclerc, 2008

The ways in which management teams and employees who participate in management processes, particularly decision-making, address the aforementioned organizational, managerial, adaption and evaluation requirements should be structured around the following four categories of results:

• Service delivery results: public service improvement plans, which are directly related to the physical and perceptual attributes of the services made available to citizens (general public and businesses), should translate into courteous greetings, shorter waiting or response times, secure service, absolute confidentiality, better access, and so forth. Quality standards should be set and implemented so that results can be measured and assessed according to clearly defined service delivery indicators, which have been made public, are understood and can be systematically adjusted;

• Management results: management results, which are related to an organization's internal processes (activities, tasks, interdependencies, roles and responsibilities, costs and delays), reflect the managerial capacity of management team members and other employees to design, implement and adjust practices and tools for converting the resources at their disposal into goods and services that can be delivered to the public, businesses or institutions. For example, improving employees' working conditions, optimizing administrative business processes, organizing work and establishing criteria for making investment choices and for recruiting and retaining qualified employees are all results that can be put forward in response to the changes called for by taxpayers and their institutional representatives regarding performance, as measured by indicators of not only a public organization's external efficiency but also its internal efficiency;

• Policy (or strategic change) results: policy results, which are based on accomplishments flowing from the strategic choices, restructurings, ambitious projects, business process reviews and so forth carried out by management, must, by their very nature, be taken into account over the medium and the long term. Such results ensure the sustainability of public organizations. In addition, since they derive from decisions made at the highest echelons of these organizations and take the political, economic, sectoral, organizational and managerial context into account, they have a determining impact on results pertaining to the delivery of services to the public and the organization's management. For instance, the coherence and clarity of the strategic choices advocated by senior management, the relevance of projects chosen by management within the framework of deliberate strategies and the kind of impact that strategic decisions are expected to have are all policy results that a management team can use to justify the leeway it needs in negotiating means and resources with prudent political decision makers or headquarter bureaucrats.

• Overall improvement results: In short, overall performance can be evaluated by measuring the quality of services delivered to citizens or institutions, ensuring optimal use of the resources and means placed at an organization's disposal and determining, in a transparent and accountable manner, the impact of the strategic choices made by management. In other words, systematic and periodic assessments of an organization in regard to both its service delivery results and its operational and strategic management targets make it possible to assess its overall performance. For example, if systematic evaluations by independent stakeholders (Office of the Auditor General, auditing firm, researchers, etc.) show that targeted improvements have been made by providing access to the healthcare services of a public hospital, successfully deploying an integrated operations information system and implementing one or more organizational projects aimed at continuous optimization of administrative processes, this will mean that the organization has achieved overall improvement results.

By arriving at a judicious combination of the results categories defined above, the management teams of public organizations will ideally achieve real leeway in the periodic negotiations entailed by the contractual logic that underpins MBR.

Lastly, from a semantic standpoint, it is important to note the difference between MBR, which advocates the use of results as a means, and RBM, which implies that results should be considered an end in themselves in a government performance management process.

Bibliography

Carroll, B. W. (2003). “Some Obstacles to Measuring Results,” Optimum, The Journal of Public Sector Management, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 41-47.

Côté, L. and B. Mazouz (2005). Les effets de la Loi sur l'administration publique sur la qualité des services et sur la gestion dans les ministères et les organismesm, www.tresor.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/PDF/publications/effets_LAP.pdf (last retrieved in September 2010).

Deschênes, T.-C. and P. Sarault (1994). “Whitehall en ebullition: ‘The Next Steps,'” Sources-ENAP, vol. 10, no. 3.

English, J. and E. Lindquist (1998). Performance Management: Linking Results to Public Debate, Toronto, Institute of Public Administration of Canada.

Jobin, M.-H. (2005). La gestion axée vers les résultats : un levier pour une plus grande performance des établissements en santé, http://web.hec.ca/sites/ceto/fichiers/ACFqdZcnk.pdf (last retrieved in September 2010).

Jorjani, H. (1998). “Demystifying Results-Based Performance Measurement,” The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 61-95.

Long, E. and A. L. Franklin (2004). “The Paradox of Implementing the Government Performance and Results Act: Top-down Direction for Bottom-up Implementation,” Public Administration Review, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 309-319.

Mazouz, B. (2008). Le métier de gestionnaire public à l'aube de la gestion par résultats, Sainte-Foy, Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Mazouz, B. and J. Leclerc (2008). La gestion intégrée par résultats, Sainte-Foy, Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Mazouz, B. and C. Rochet (2005). “De la gestion par résultats et de son institutionnalisation: quelques enseignements préliminaires tirés des expériences françaises et québécoises,” Télescope, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 69-85.

Mazouz, B. and M. J. B. Tardif (2010). “À propos de la performance : l'Arlésienne de la sphère publique,” in D. Proulx, Management des organisations publiques, 2nd ed., Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Mazouz, B. and B. Tremblay (2006). “Toward a Postbureaucratic Model of Governance: How Institutional Commitment Is Challenging Quebec's Administration,” Public Administration Review, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 263-273.

Vérificateur général du Québec (1999). La gestion par résultats : les conditions favorables à son implantation, www.vgq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/fr_publications/fr_rapport-annuel/fr_1998-1999-T2/fr_Rapport1998-1999-T2-AnnexeA.pdf (last retrieved in September 2010).

Voyer, P. (1999). Tableaux de bord de gestion et indicateurs de performance, Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec.

_______________________

Reproduction

Reproduction in whole or part of the definitions contained in the Encyclopedic Dictionary of Public Administration is authorized, provided the source is acknowledged.

How to cite

Mazouz, B. (2012). “Management by Results,” in L. Côté and J.-F. Savard (eds.), Encyclopedic Dictionary of Public Administration, [online], www.dictionnaire.enap.ca

Legal deposit

Library and Archives Canada, 2012 | ISBN 978-2-923008-70-7 (Online)